Good morning. Two measurements tell two stories about the strength of U.S. employment.

An office in Manhattan this year. Jeenah Moon for The New York Times

Job alerts

Here’s something pretty much anyone who follows economic data closely can agree on: The U.S. labor market is hot, but cooling.

What’s less clear is just how hot it is, or how fast it’s cooling down. That question matters a lot to Federal Reserve policymakers trying to find a way to bring inflation under control without causing a recession. In today’s newsletter, I want to take you through two measures that offer subtly but importantly different answers. Consider this chart:

Data is through September 2022 and seasonally adjusted. | Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

The top line, in blue, shows the number of job openings that employers are trying to hire workers for. It shows a labor market that is extraordinarily strong and has only recently begun to cool. The bottom line, in yellow, shows the number of people who voluntarily quit their jobs each month. Many economists consider that statistic to be a key barometer of the strength of the labor market. It suggests the labor market is strong, and not so far out of line with historical patterns.

I’ll explain more about these numbers and why I’m highlighting them in a moment. First, though, it’s worth understanding why these questions matter in the first place.

Supply and demand

The biggest problem facing the economy right now is that prices are rising much too quickly. That dynamic stems partly from the lingering effects of the pandemic, which continue to disrupt international supply chains, and global forces, like the war in Ukraine, which has pushed up the price of food and energy. Most economists agree that rapid inflation is also at least partly the result of excessive demand: American consumers want more cars, airline tickets and restaurant meals than companies can produce, pushing up prices.

The Fed is trying to tamp down demand by raising interest rates, which makes borrowing money more expensive for consumers and businesses. Yesterday, the central bank announced it would raise rates by three-quarters of a point for the fourth time since June.

That move was widely expected. But experts are less in agreement about what the Fed will do in the months ahead. Some economists argue it should hold off on further rate increases and see whether inflation begins to ease. Others say the Fed should keep going until its efforts clearly have an effect.

Which path policymakers choose depends in part on how Jerome Powell, the Fed chair, and his colleagues view the labor market. If companies keep adding jobs and raising pay, inflation is likely to remain high, and the Fed is likely to remain aggressive in its fight to tame it. If job growth stalls and unemployment rises, the Fed could pause sooner to avoid causing a recession.

So far, the Fed seems firmly on the side of those who see the job market as too hot. Powell said yesterday that any talk of a pause in rate increases is “premature.”

Job openings

For the past year, the Fed has been focused on one measure of the labor market in particular: job openings. Powell has repeatedly noted that there are roughly twice as many vacant jobs as unemployed workers available to fill them.

The logic behind Powell’s attention on job openings is simple. They are a direct measure of demand, since employers typically don’t try to hire when no one is buying their products. And they have a clear connection to wage growth — and therefore inflation — because when lots of companies are hiring, they have to pay more to compete for workers.

Fed officials have been hoping that as interest rates rise, companies would respond by cutting back on recruitment. So far, we’ve seen only limited evidence of such a trend.

Some economists, however, have begun questioning the Fed’s focus on job openings. Other signals, like the unemployment rate, show the labor market is strong, but not nearly as strong as openings would imply.

Quitting time

Which brings us to our second indicator: what economists call quits.

You probably read about the “great resignation,” the surge in people leaving their jobs as the economy re-emerged from Covid-induced lockdowns. The phenomenon was real, but the narrative often missed a crucial element: Most weren’t quitting to sit on the couch. They were taking other, usually better-paying, jobs.

Economists see quitting as a sign of confidence among workers: Changing jobs is a risk, so people avoid doing so if they’re worried about the economy. And since people typically don’t jump employers without a bump in pay, job-switching contributes to wage growth. Data released yesterday from ADP, the payroll-processing giant, showed that people who switched jobs in October saw their pay rise roughly twice as quickly as people who stayed put.

In late 2020 and early 2021, resignations and job openings rose roughly in tandem. But then the number of people quitting began to level off, even as openings kept rising. Americans are still changing jobs more than they were before the pandemic, but only modestly so.

So if openings suggest the labor market is a raging inferno, resignations imply it is more like an uncomfortably hot day.

More economic news

The Fed will continue to raise interest rates, though more gradually. (Here are takeaways from its announcement.)

Why are mortgage rates so high? Blame the Fed, Wall Street and your neighbor.

Republicans have embraced plans to limit Social Security and Medicare.

Continue reading the main story

THE LATEST NEWS

Midterms

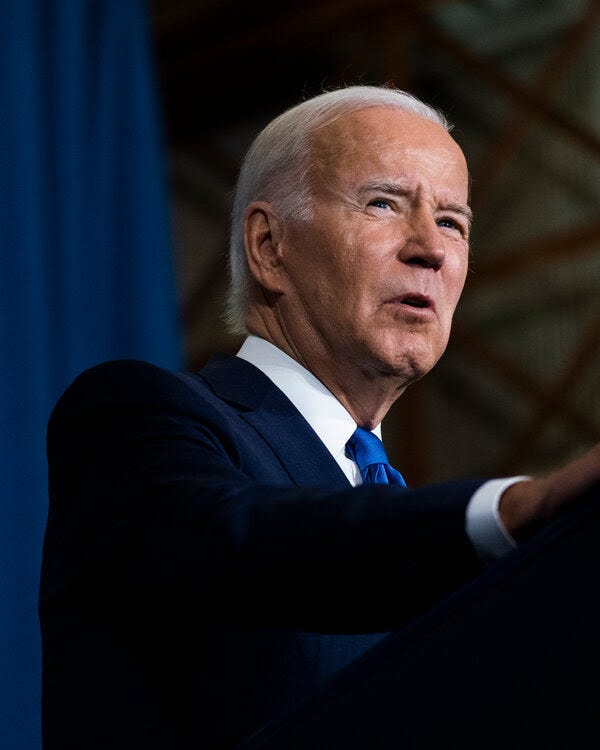

President Biden last night. Pete Marovich for The New York Times

President Biden denounced Republicans for encouraging political violence and called their refusals to commit to accepting election results a “path to chaos.” Follow our midterm updates.

CONTEXT: The linked article above that covered Biden’s speech did not provide any examples or sources of Republicans encouraging political violence. Instead, the article and the President’s comments are reaching to correlate Republican talking points with political violence, without proof.

Mike Pence is campaigning for Republicans in battleground states, elevating his visibility for a potential 2024 presidential campaign.

As Republicans attack Biden’s immigration policies, some Democrats in close races are calling for more border enforcement.

In Wisconsin, the midterms are as much about the next presidential election as they are about 2022.

Voting machines aren’t rigged and voter fraud isn’t rampant. The Times debunked five election myths.

CONTEXT: This linked article is more of an opinion piece, in that it provides the reader with virtually no actual data, except linking to articles written by the Associated Press, which provided little-to-no definitive data that debunked voter fraud claims.

War in Ukraine

A checkpoint in Kharkiv, Ukraine, this week.Finbarr O'Reilly for The New York Times

The U.S. accused North Korea of shipping a “significant number” of artillery shells to Russia to aid its military in Ukraine.

After a dayslong pause, Russia said it was rejoining a deal that allows the shipment of grain from Ukrainian ports.

Apprehension, but also beauty: Kyiv’s streets are dark because of restrictions on electricity.

International

Ethiopia’s government and forces in the country’s northern Tigray region agreed to end a two-year civil war that has killed hundreds of thousands of people.

Tens of thousands of Brazilians protested President Jair Bolsonaro’s election defeat, massing outside military bases to demand that troops step in to prevent a transfer of power.

Benjamin Netanyahu will likely become Israel’s prime minister again today, putting far-right groups at the heart of the country’s political system.

Other Big Stories

CVS and Walgreens agreed to pay about $5 billion each to settle thousands of lawsuits over the opioid crisis.

Les Moonves, the former chief of CBS, and the network’s parent company agreed to pay $9.75 million to settle a case related to sexual misconduct claims against him.

Flawed pulse oximeters may have contributed to Covid deaths, doctors warned.

Opinions

Julie Powell helped make food writing less preachy and more populist, Frank Bruni writes.

An Ebola outbreak in Uganda is a chance for health officials everywhere to regain the public’s trust, Henry Kyobe Bosa argues.

Tom Brady and Gisele Bündchen’s split echoes a pattern: In straight marriages, it’s often the woman’s career that suffers, Elizabeth Spiers says.